Architectural Record, the authoritative architecture magazine, exclusively featured Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum

2021.07.26

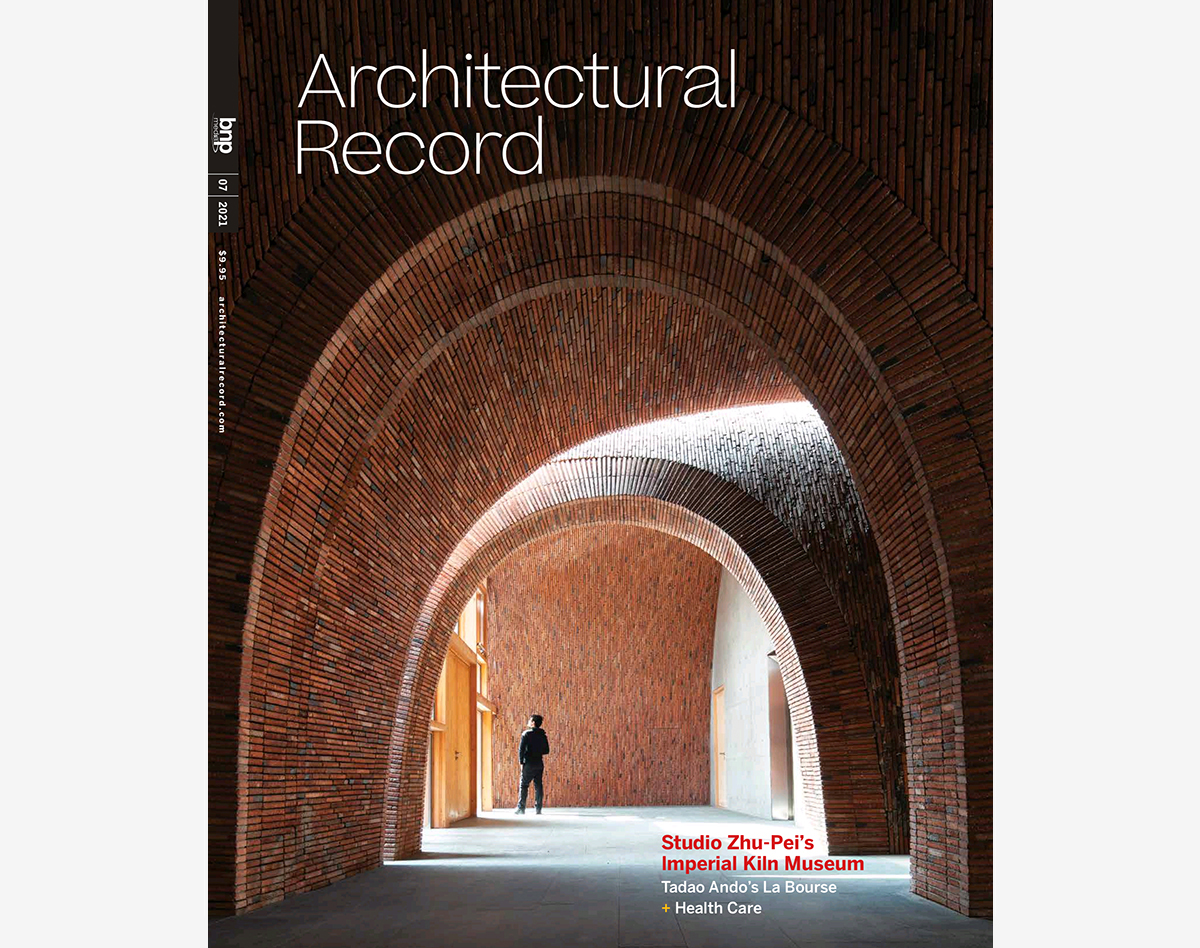

The Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum by Studio Zhu Pei has been selected as the cover and exclusively featured in the July 2021 issue of Architectural Record, one of the leading architectural design magazines in the world.

Founded in 1891, Architectural Record is the #1 source for news and information about architecture and design. Throughout its 130 years, the award-winning publication has fostered readership among architecture, engineering, and design professionals by covering noteworthy and innovative projects in the United States and across the globe. It is also a designated architectural reading by the American Institute of Architects (AIA). This time, Architectural Record invited the famous architectural design curator Aric Chen to visit Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum on site and write a feature article.

Treasure Chest

The Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum by Studio Zhu Pei celebrates a Chinese craft and tradition.

Author: Aric Chen

Aric Chen is the General and Artistic Director of Rotterdam's Het Nieuwe Instituut and an independent curator and writer based in Shanghai, where he is a professor of practice and director of the Curatorial Lab at the College of Design and Innovation at Tongji University. Chen was also the Curatorial Director of the Design Miami, the founding lead curator for design and architecture at M+ Museum in Hong Kong. He has earned an international reputation as an independent curator, working with museums, biennials, and other venues globally.

Straddling the Chang River in an area once replete with kaolin, the long-secret critical ingredient of porcelain, Jingdezhen—in the landlocked Chinese province of Jiangxi—has been China's center for creating the exquisite translucent ceramic for well over a millennium.

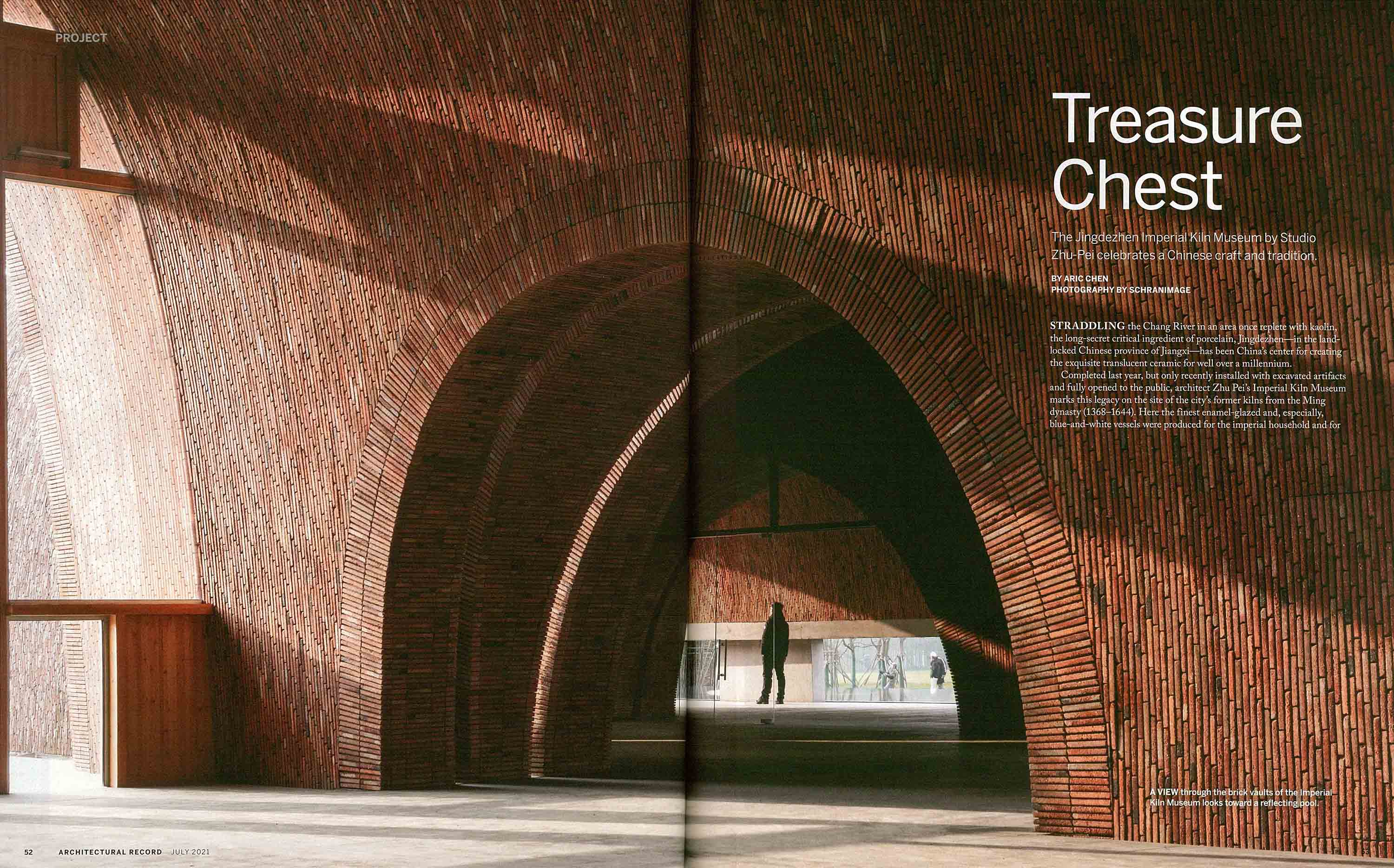

Completed last year, but only recently installed with excavated artifacts and fully opened to the public, architect Zhu Pei's Imperial Kiln Museum marks this legacy on the site of the city's former kilns from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Here the finest enamel-glazed and, especially, blue-and-white vessels were produced for the imperial household and for export during one of the heights of the art in China. “It's a place of historic significance,” the Beijing-based architect says.

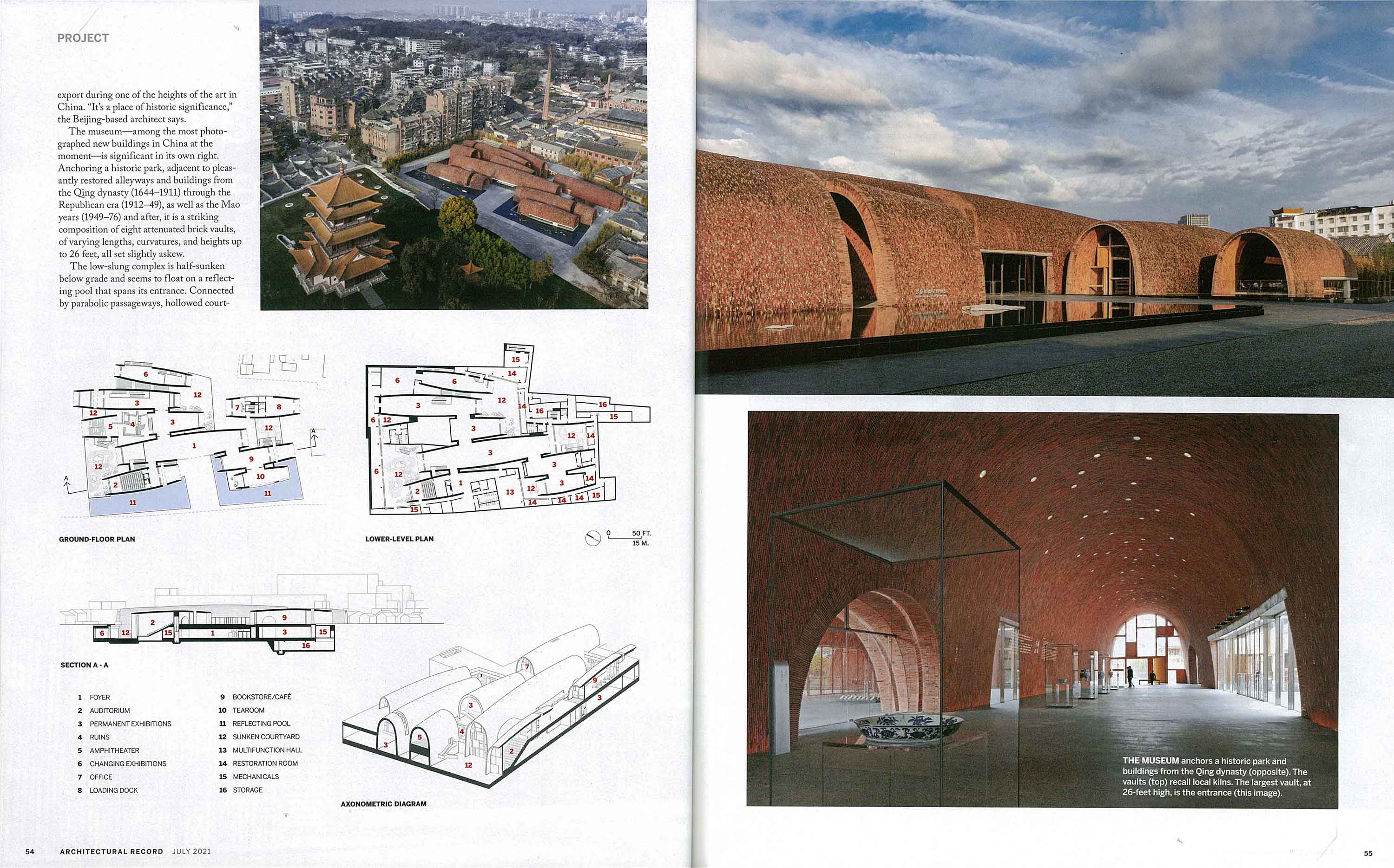

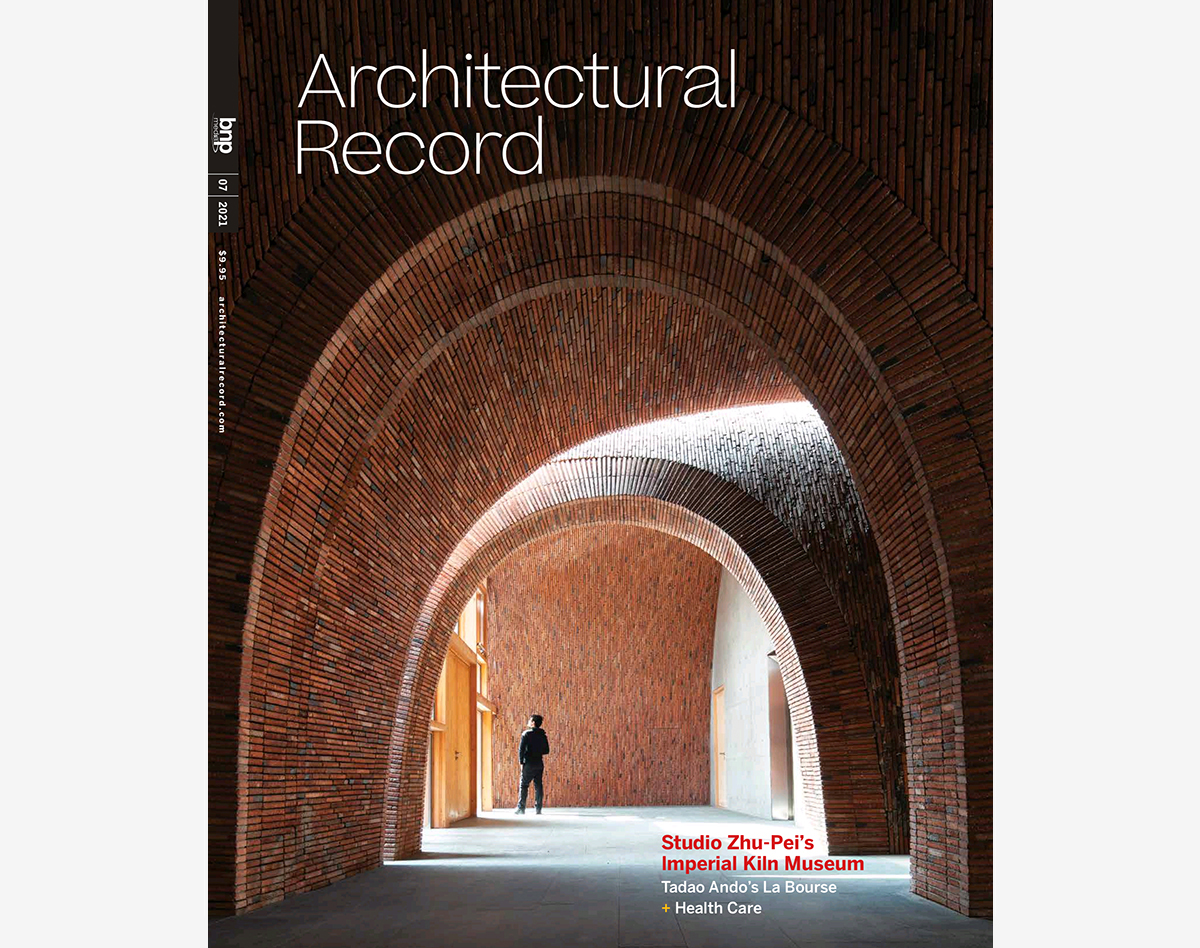

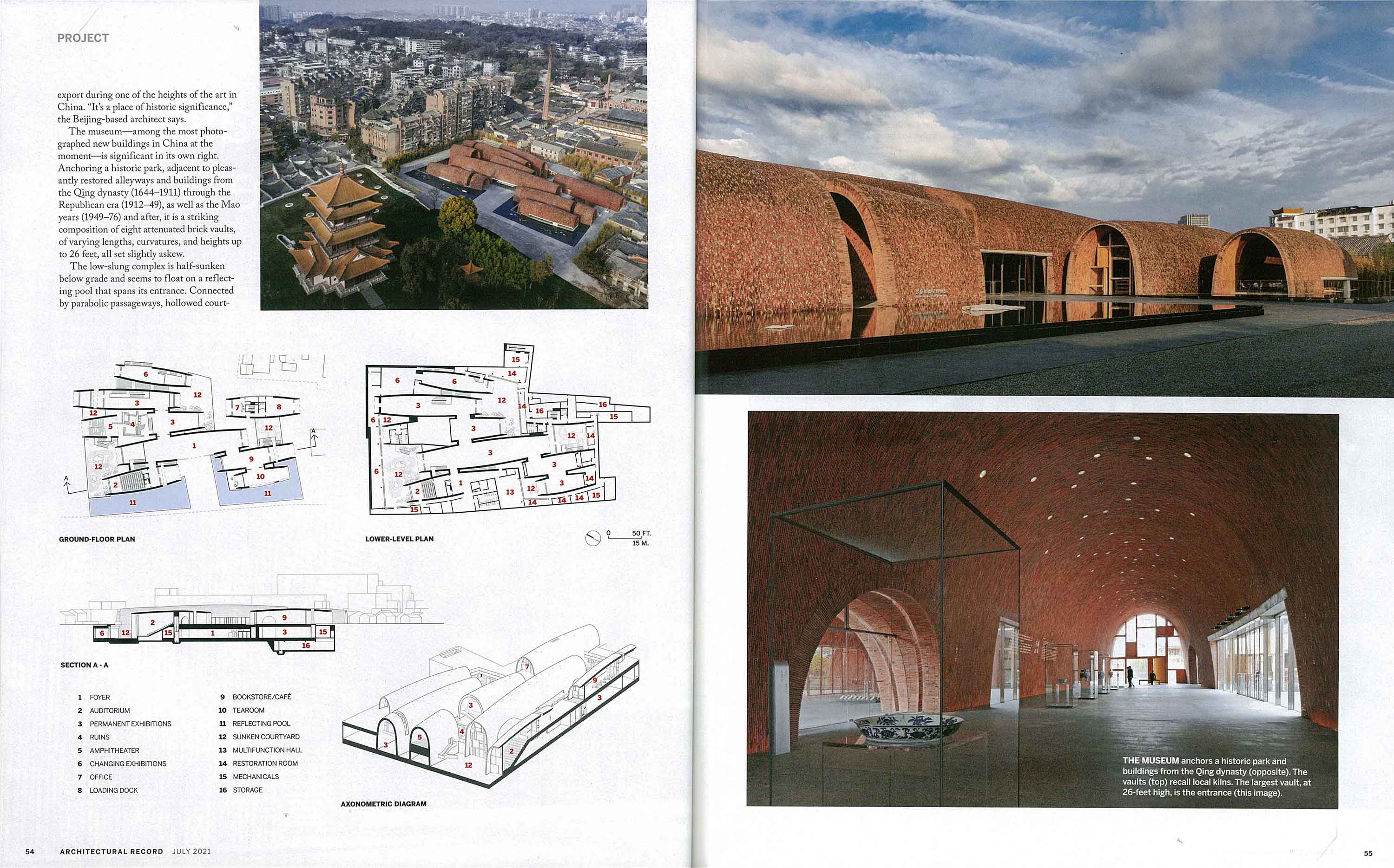

The museum—among the most photographed new buildings in China at the moment—is significant in its own right. Anchoring a historic park, adjacent to pleasantly restored alleyways and buildings from the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) through the Republican era (1912–49), as well as the Mao years (1949–76) and after, it is a striking composition of eight attenuated brick vaults, of varying lengths, curvatures, and heights up to 26 feet, all set slightly askew.

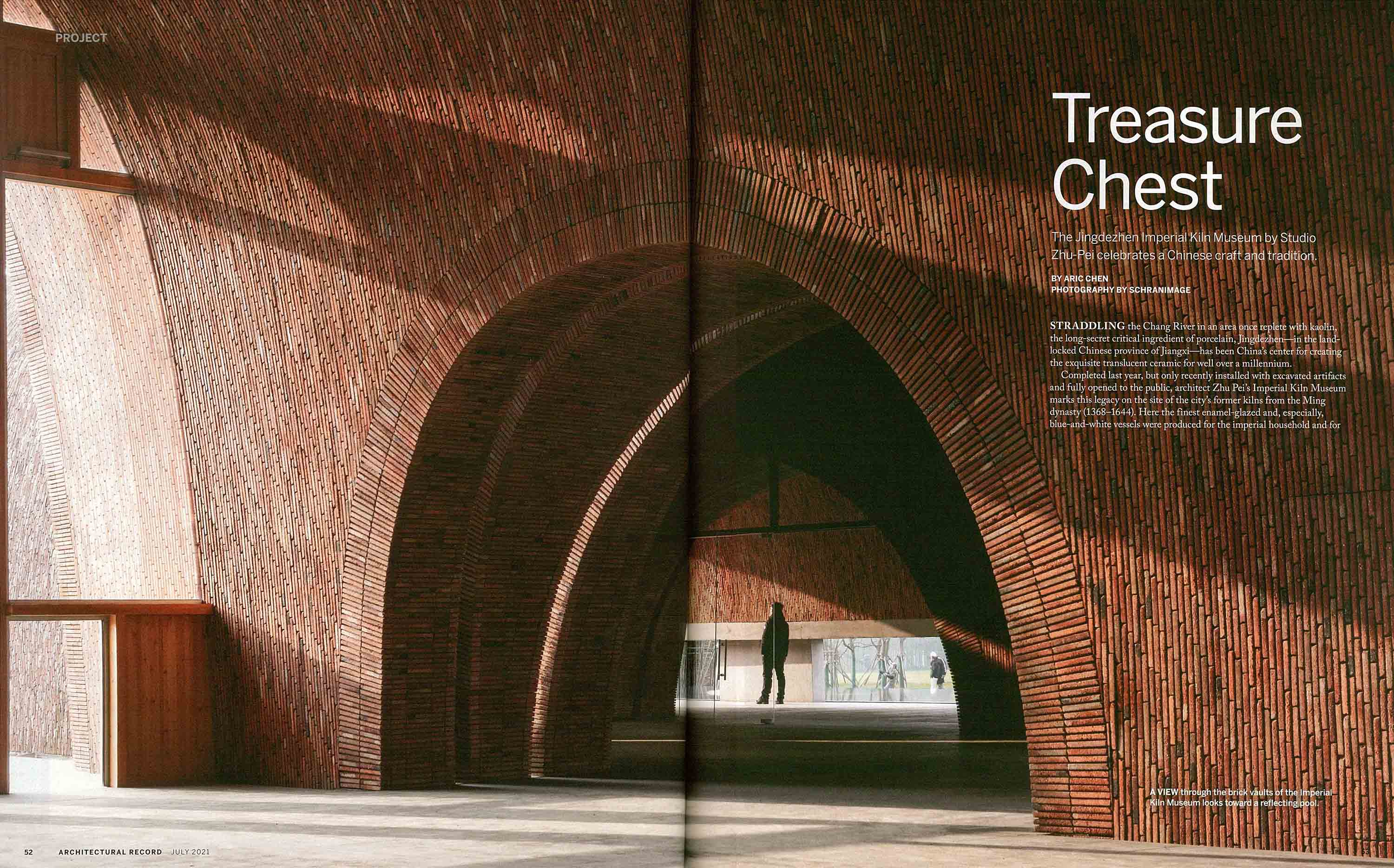

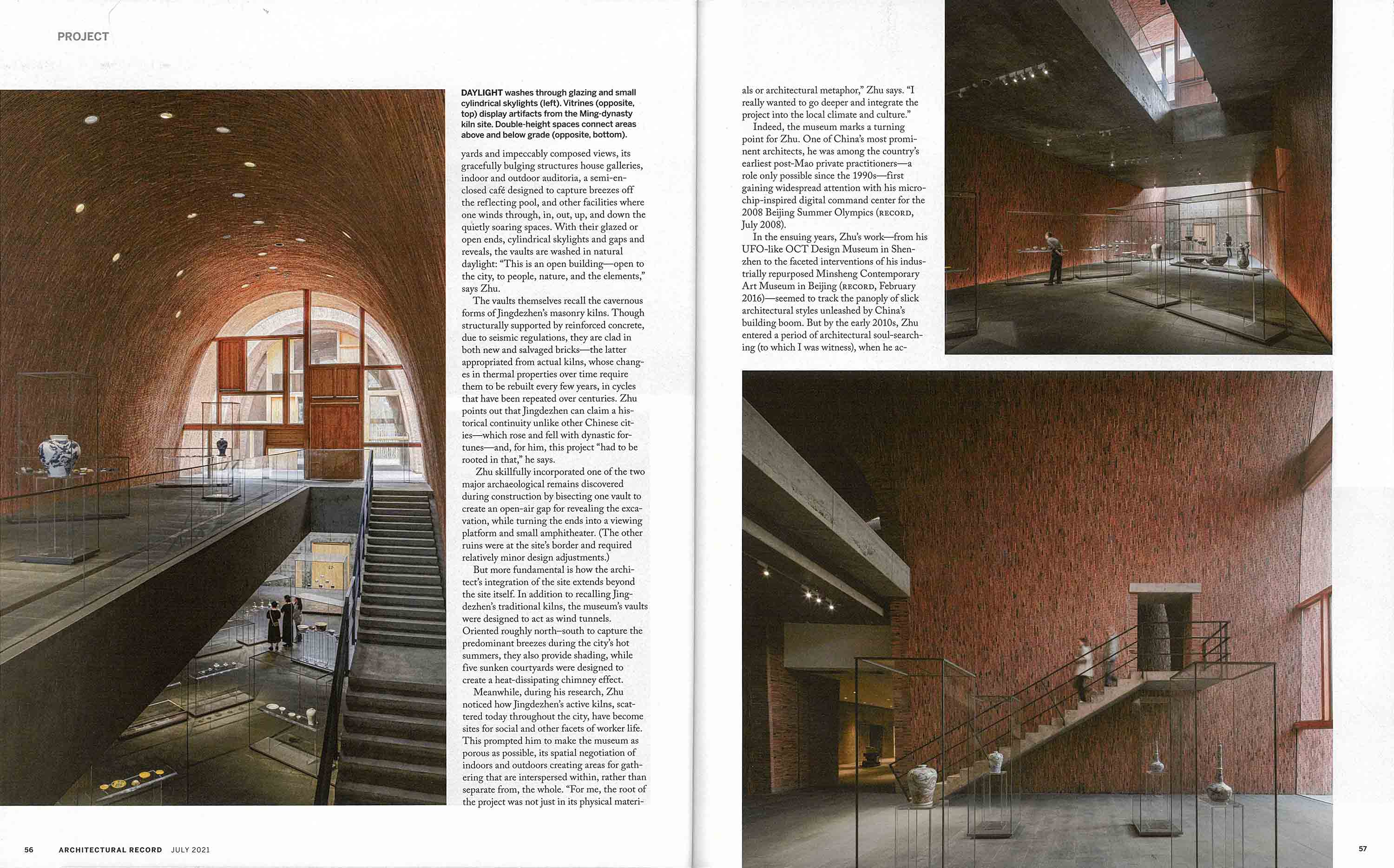

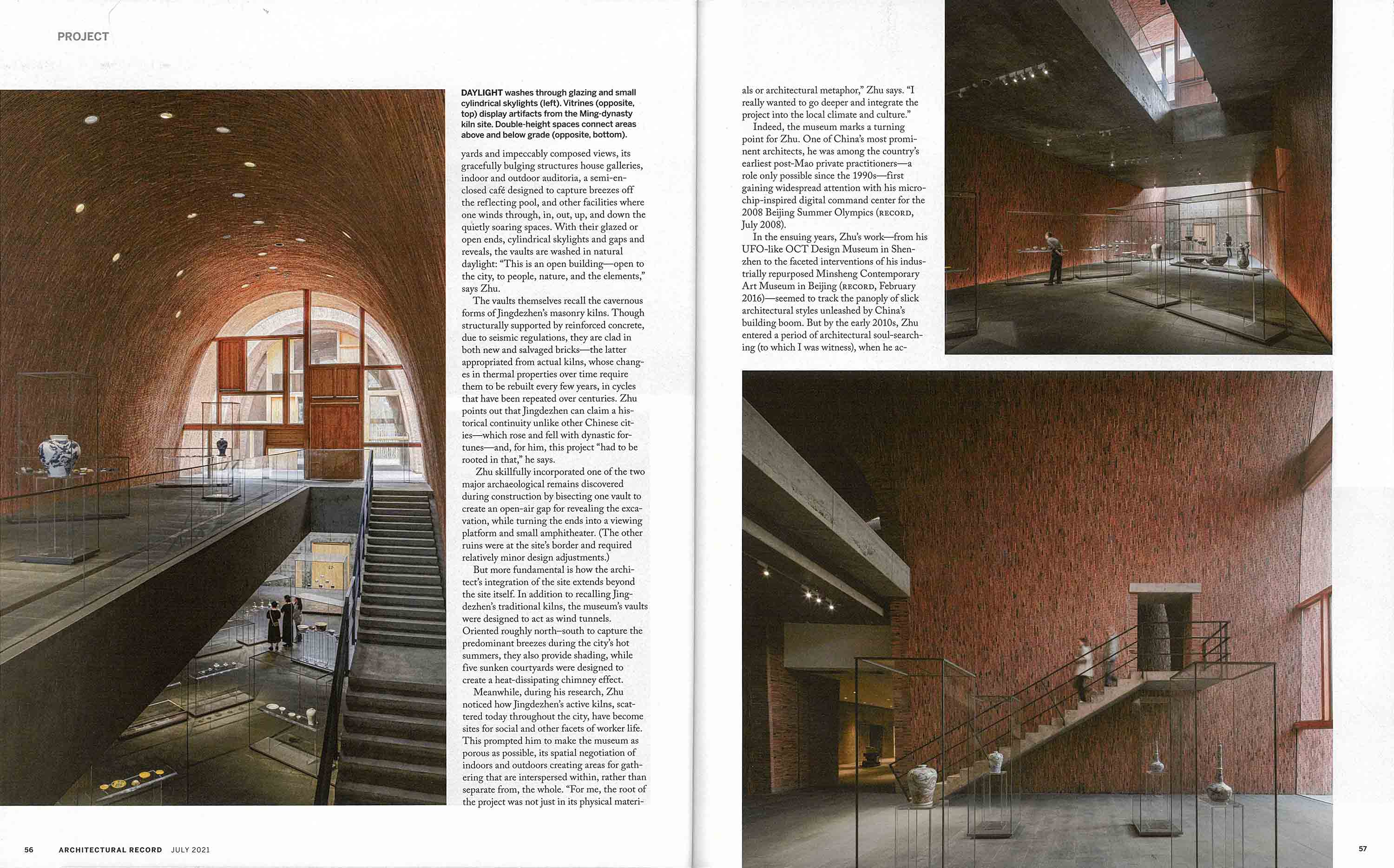

The low-slung complex is half-sunken below grade and seems to float on a reflecting pool that spans its entrance. Connected by parabolic passageways, hollowed court yards and impeccably composed views, its gracefully bulging structures house galleries, indoor and outdoor auditoria, a semi-enclosed café designed to capture breezes off the reflecting pool, and other facilities where one winds through, in, out, up, and down the quietly soaring spaces. With their glazed or open ends, cylindrical skylights and gaps and reveals, the vaults are washed in natural daylight: “This is an open building—open to the city, to people, nature, and the elements,” says Zhu.

The vaults themselves recall the cavernous forms of Jingdezhen’s masonry kilns. Though structurally supported by reinforced concrete, due to seismic regulations, they are clad in both new and salvaged bricks—the latter appropriated from actual kilns, whose changes in thermal properties over time require them to be rebuilt every few years, in cycles that have been repeated over centuries. Zhu points out that Jingdezhen can claim a historical continuity unlike other Chinese cities—which rose and fell with dynastic fortunes—and, for him, this project “had to be rooted in that,” he says.

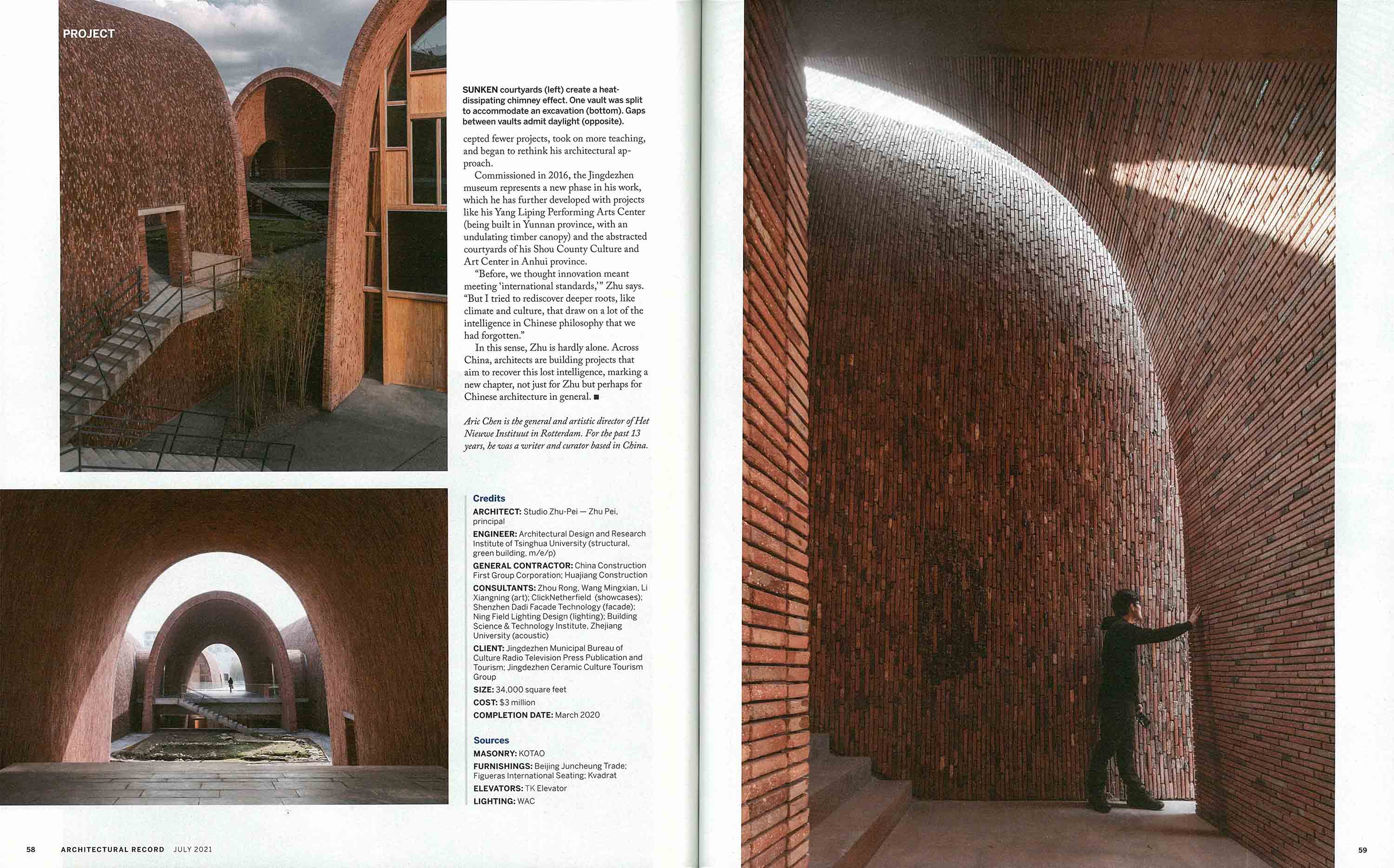

Zhu skillfully incorporated one of the two major archaeological remains discovered during construction by bisecting one vault to create an open-air gap for revealing the excavation, while turning the ends into a viewing platform and small amphitheater. (The other ruins were at the site's border and required relatively minor design adjustments.)

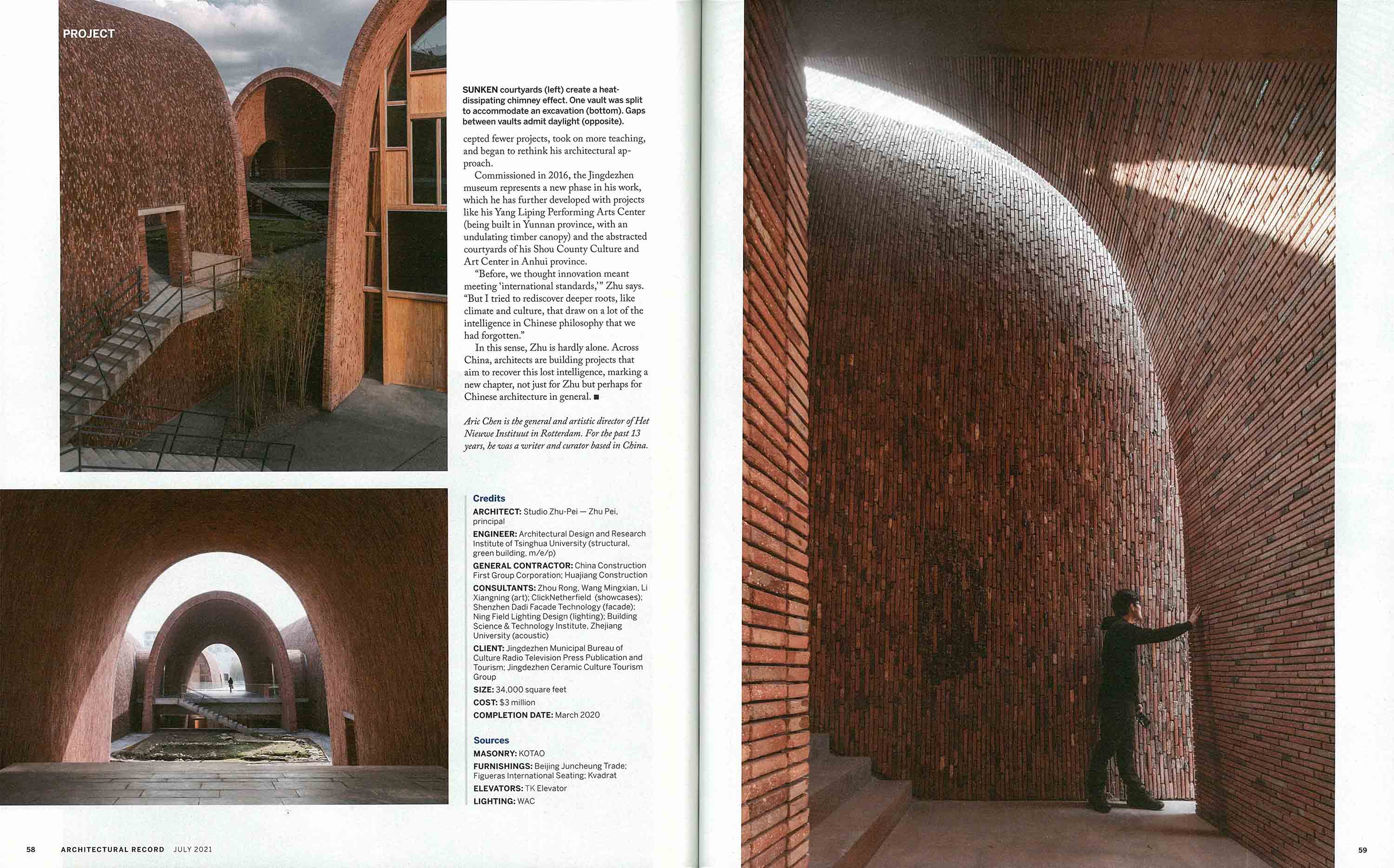

But more fundamental is how the architect's integration of the site extends beyond the site itself. In addition to recalling Jingdezhen's traditional kilns, the museum's vaults were designed to act as wind tunnels. Oriented roughly north–south to capture the predominant breezes during the city's hot summers, they also provide shading, while five sunken courtyards were designed to create a heat-dissipating chimney effect.

Meanwhile, during his research, Zhu noticed how Jingdezhen's active kilns, scattered today throughout the city, have become sites for social and other facets of worker life. This prompted him to make the museum as porous as possible, its spatial negotiation of indoors and outdoors creating areas for gathering that are interspersed within, rather than separate from, the whole. “For me, the root of the project was not just in its physical materials or architectural metaphor,” Zhu says. “I really wanted to go deeper and integrate the project into the local climate and culture.”

Indeed, the museum marks a turning point for Zhu. One of China's most prominent architects, he was among the country's earliest post-Mao private practitioners—a role only possible since the 1990s—first gaining widespread attention with his microchip-inspired digital command center for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics.

In the ensuing years, Zhu's work—from his UFO-like OCT Design Museum in Shenzhen to the faceted interventions of his industrially repurposed Minsheng Contemporary Art Museum in Beijing—seemed to track the panoply of slick architectural styles unleashed by China’s building boom. But by the early 2010s, Zhu entered a period of architectural soul-searching (to which I was witness), when he accepted fewer projects, took on more teaching, and began to rethink his architectural approach.

Commissioned in 2016, the Jingdezhen museum represents a new phase in his work, which he has further developed with projects like his Yang Liping Performing Arts Center (being built in Yunnan province, with an undulating timber canopy) and the abstracted courtyards of his Shou County Culture and Art Center in Anhui province.

“Before, we thought innovation meant meeting ‘international standards,’ ”Zhu says. “But I tried to rediscover deeper roots, like climate and culture, that draw on a lot of the intelligence in Chinese philosophy that we had forgotten.”

In this sense, Zhu is hardly alone. Across China, architects are building projects that aim to recover this lost intelligence, marking a new chapter, not just for Zhu but perhaps for Chinese architecture in general.

Architectural Record, the authoritative architecture magazine, exclusively featured Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum

2021.07.26

The Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum by Studio Zhu Pei has been selected as the cover and exclusively featured in the July 2021 issue of Architectural Record, one of the leading architectural design magazines in the world.

Founded in 1891, Architectural Record is the #1 source for news and information about architecture and design. Throughout its 130 years, the award-winning publication has fostered readership among architecture, engineering, and design professionals by covering noteworthy and innovative projects in the United States and across the globe. It is also a designated architectural reading by the American Institute of Architects (AIA). This time, Architectural Record invited the famous architectural design curator Aric Chen to visit Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum on site and write a feature article.

Treasure Chest

The Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum by Studio Zhu Pei celebrates a Chinese craft and tradition.

Author: Aric Chen

Aric Chen is the General and Artistic Director of Rotterdam's Het Nieuwe Instituut and an independent curator and writer based in Shanghai, where he is a professor of practice and director of the Curatorial Lab at the College of Design and Innovation at Tongji University. Chen was also the Curatorial Director of the Design Miami, the founding lead curator for design and architecture at M+ Museum in Hong Kong. He has earned an international reputation as an independent curator, working with museums, biennials, and other venues globally.

Straddling the Chang River in an area once replete with kaolin, the long-secret critical ingredient of porcelain, Jingdezhen—in the landlocked Chinese province of Jiangxi—has been China's center for creating the exquisite translucent ceramic for well over a millennium.

Completed last year, but only recently installed with excavated artifacts and fully opened to the public, architect Zhu Pei's Imperial Kiln Museum marks this legacy on the site of the city's former kilns from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Here the finest enamel-glazed and, especially, blue-and-white vessels were produced for the imperial household and for export during one of the heights of the art in China. “It's a place of historic significance,” the Beijing-based architect says.

The museum—among the most photographed new buildings in China at the moment—is significant in its own right. Anchoring a historic park, adjacent to pleasantly restored alleyways and buildings from the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) through the Republican era (1912–49), as well as the Mao years (1949–76) and after, it is a striking composition of eight attenuated brick vaults, of varying lengths, curvatures, and heights up to 26 feet, all set slightly askew.

The low-slung complex is half-sunken below grade and seems to float on a reflecting pool that spans its entrance. Connected by parabolic passageways, hollowed court yards and impeccably composed views, its gracefully bulging structures house galleries, indoor and outdoor auditoria, a semi-enclosed café designed to capture breezes off the reflecting pool, and other facilities where one winds through, in, out, up, and down the quietly soaring spaces. With their glazed or open ends, cylindrical skylights and gaps and reveals, the vaults are washed in natural daylight: “This is an open building—open to the city, to people, nature, and the elements,” says Zhu.

The vaults themselves recall the cavernous forms of Jingdezhen’s masonry kilns. Though structurally supported by reinforced concrete, due to seismic regulations, they are clad in both new and salvaged bricks—the latter appropriated from actual kilns, whose changes in thermal properties over time require them to be rebuilt every few years, in cycles that have been repeated over centuries. Zhu points out that Jingdezhen can claim a historical continuity unlike other Chinese cities—which rose and fell with dynastic fortunes—and, for him, this project “had to be rooted in that,” he says.

Zhu skillfully incorporated one of the two major archaeological remains discovered during construction by bisecting one vault to create an open-air gap for revealing the excavation, while turning the ends into a viewing platform and small amphitheater. (The other ruins were at the site's border and required relatively minor design adjustments.)

But more fundamental is how the architect's integration of the site extends beyond the site itself. In addition to recalling Jingdezhen's traditional kilns, the museum's vaults were designed to act as wind tunnels. Oriented roughly north–south to capture the predominant breezes during the city's hot summers, they also provide shading, while five sunken courtyards were designed to create a heat-dissipating chimney effect.

Meanwhile, during his research, Zhu noticed how Jingdezhen's active kilns, scattered today throughout the city, have become sites for social and other facets of worker life. This prompted him to make the museum as porous as possible, its spatial negotiation of indoors and outdoors creating areas for gathering that are interspersed within, rather than separate from, the whole. “For me, the root of the project was not just in its physical materials or architectural metaphor,” Zhu says. “I really wanted to go deeper and integrate the project into the local climate and culture.”

Indeed, the museum marks a turning point for Zhu. One of China's most prominent architects, he was among the country's earliest post-Mao private practitioners—a role only possible since the 1990s—first gaining widespread attention with his microchip-inspired digital command center for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics.

In the ensuing years, Zhu's work—from his UFO-like OCT Design Museum in Shenzhen to the faceted interventions of his industrially repurposed Minsheng Contemporary Art Museum in Beijing—seemed to track the panoply of slick architectural styles unleashed by China’s building boom. But by the early 2010s, Zhu entered a period of architectural soul-searching (to which I was witness), when he accepted fewer projects, took on more teaching, and began to rethink his architectural approach.

Commissioned in 2016, the Jingdezhen museum represents a new phase in his work, which he has further developed with projects like his Yang Liping Performing Arts Center (being built in Yunnan province, with an undulating timber canopy) and the abstracted courtyards of his Shou County Culture and Art Center in Anhui province.

“Before, we thought innovation meant meeting ‘international standards,’ ”Zhu says. “But I tried to rediscover deeper roots, like climate and culture, that draw on a lot of the intelligence in Chinese philosophy that we had forgotten.”

In this sense, Zhu is hardly alone. Across China, architects are building projects that aim to recover this lost intelligence, marking a new chapter, not just for Zhu but perhaps for Chinese architecture in general.